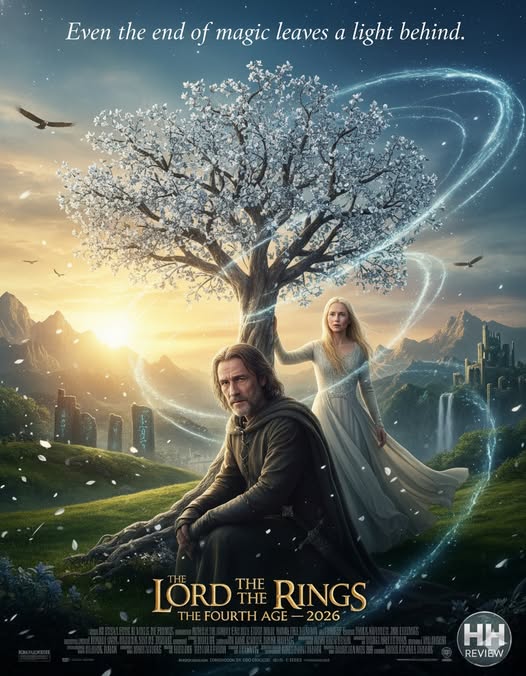

The Lord of the Rings: The Fourth Age (2026)

The age of heroes ends, but their silence still sings. The Lord of the Rings: The Fourth Age (2026) is not a sequel — it is an elegy. A final hymn to a world that once trembled under gods and giants, and now bows to time itself.

Viggo Mortensen returns as Aragorn, no longer the crowned savior, but a weary monarch watching his kingdom fade into legend. His reign has brought peace, but peace carries its own weight — the quiet corrosion of purpose. In his eyes, we see a man haunted not by battle, but by the unbearable stillness that follows victory.

Cate Blanchett’s Galadriel stands at his side like a fading constellation — luminous, ethereal, and achingly aware of her own vanishing. The film’s greatest power lies in her silence; she embodies the sorrow of immortality outlasting meaning. When she whispers, “Even light must rest,” it’s less prophecy, more confession.

Directed with solemn grandeur by Denis Villeneuve, this installment transforms Middle-earth into a meditation on impermanence. The lands are the same, yet not — the mountains quieter, the forests paler, the songs of the elves reduced to echoes on the wind. The cinematography is vast and mournful, draped in silver dawns and dying sunsets. Every frame feels like the world exhaling its last breath of magic.

There are no grand wars here — only tremors of myth dissolving into memory. The men of Gondor rebuild, but their towers no longer reach for the heavens. The elves depart across the sea, leaving the air thinner, the color of the world dimmer. Even the Shire, once vibrant, feels subdued — its peace tinged with the melancholy of forgetting.

Mortensen gives the performance of his career — regal yet fragile, his every movement laced with reverence and regret. Aragorn’s dialogue is sparse, each line deliberate, carved from the weight of time. He’s not fighting darkness anymore, but the fading of the dawn.

Blanchett, meanwhile, is transcendent. Galadriel’s glow is softer now, her grace weary, her wisdom tinged with grief. Their scenes together — filled with unspoken reverence — are less about love, more about shared extinction. Two beings standing on opposite shores of eternity, both aware the tide is rising.

The film’s score, composed by Howard Shore in collaboration with Ramin Djawadi, is a masterwork — a requiem of fading choirs and ghostly strings. It carries the echo of ancient songs, now half-remembered, as if Middle-earth itself were mourning its own story.

By the final act, the world begins to fold into history. Magic retreats. Memory becomes myth. A single star — the last of Eärendil’s light — remains in the sky, refusing to dim. As Aragorn takes his final breath, the narration whispers, “What was once forever, now becomes a tale.”

The screen fades to black — and for a moment, silence reigns. But in that silence, you hear it: the faint hum of an age refusing to die.

The Fourth Age is not about ending — it’s about the courage to fade with grace. A masterpiece of sorrow and splendor, it reminds us that every world — even one born of stars — must someday dream itself to sleep.

Related movies: